Who are your ancestors?

Bring your family tree up into your mind’s eye. Who are your ancestors in that biological genetic family tree? Now, think about a different family tree. Who are your ancestors in the faith? Who reached you with the Gospel? Who reached them? So on and so on and so on until you get to the root of it!

You are the spiritual fruit of generations of Christians “passing on to others what we in turn also received.”

Your spiritual family tree is probably pretty complex and you probably don’t know how to trace it. There are some really complicated spiritual family trees out there that are related to the fact that people who understood themselves to be Christians owned other people as enslaved Americans and taught them Bible stories and catechized them.

Some of those people went on to be missionaries in places around the world where the gospel was then planted in the hearts and minds of others. It’s a complex family tree. Slavery is not just a story from history. It’s our history. It’s our story.

In 1838, Maria Fearing was born, a child of enslaved parents, near Gainesville, Alabama. The family who owned her family were Evangelical Christians who catechized those they also enslaved. That’s about as complicated as a spiritual family tree could ever get!

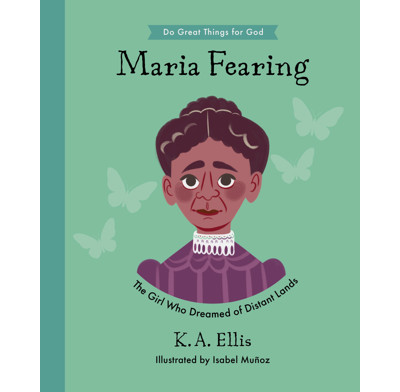

Maria Fearing became a missionary in Africa, and the lives of many people were radically transformed because of her life. To get to know the story of Maria fearing, we’re going to talk with Karen Ellis who has recently written a children’s book about Fearing’s life and faith.

Karen Ellis is the director of the Center for the Study of the Bible and Ethnicity at Reformed Theological Seminary in Atlanta, Georgia and wrote a book to share Maria Fearing’s story with the next generation, titled Maria Fearing: The Girl Who Dreamed of Distant Lands.

This is an excerpt of Carmen’s interview with KA Ellis on Mornings with Carmen, recorded on Juneteenth. To hear the full interview, listen online here at MyFaithRadio.com. The book giveaway mentioned during the show is now closed.

Karen Ellis: Maria Fearing was born enslaved on an Alabama plantation. And in 1863 when she was emancipated, she asked God, she had already been catechized, she had heard about Jesus and God and his stories of the Bible already through not just the people who owned her who catechized her, but she had also heard the marvelous stories of God’s freedom, spiritual freedom, physical freedom for the children of Israel. She had heard those stories in the hush harbors, in the secret churches, and the places where the slaves could meet at night after they had worked all day and enjoyed fellowship with each other and with God.

And so having heard about these folks and having heard about this God that she wanted to serve, she chose, upon emancipation, to move to Congo. And it is amazing the way she self-financed. She joined the first African-American led mission team to go from the United States of America. And she joined a team with the Sheppards and the Edmistons, and went there and encountered slavery herself of masses of children and adults being exploited by King Leopold II in the rubber trade and the Arab slave trade. And she began taking what she knew already of God’s concepts of spiritual and physical freedom and applied them and started ransoming children out of the rubber trade and into her home.

So here you have this middle-aged 56-year-old single woman who had come from absolutely nothing, self-funded all the way to Congo and started taking these children into her home. They loved her so much, Carmen, the children gave her a special name, which was Mama Wa Mputu, which means mother from a faraway land. And she worked so hard and so much that her denomination finally said, “You have to retire, Mama Wa Mputu. You have to come off the field.” And so she did in her seventies and she came back to the South, back to Alabama, and still taught Sunday school until she was in her nineties. And so just a wonderful story of a servant of God found in the hidden unlikely places. Talking about some themes that are difficult, but we approach them in an age appropriate way. And I’ll even tell you about some little Easter eggs that are hidden in the story and in the illustrations that if you want to expand the conversation with your children, if you think that they’re able to handle it, I’ll tell you how to do that.

Carmen: She has an extraordinary personal story, but so do other people in her story. Like William Sheppard’s story is an extraordinary story within the story. There’s a lot going on in the life of Maria Fearing. I think that when we imagine going as a missionary to a faraway land, we have romanticized that, and in many, many ways. For us as adults, can you describe what life was like in what we now call the Congo in the days of King Leopold II?

K.A.: Right. Well, this is a great point, Carmen, I’m glad you brought it up. You have an adverse climate, which would have been very, very difficult for them to adjust to. Their travel was not easy. They took a steamer ship from New York, which took many days, from New York to the Congo coast. And then they had to travel inland and it was not an easy trip. And then they lived in a climate that was very different from their own in a culture that was very different from the one they knew.

And so there was a lot of learning, a lot of adjusting on their part, but they also encountered the area, the region at a time when King Leopold II had committed horrific human rights abuses. And here’s the Easter egg I was talking about, one of his ways of punishing his forced laborers was by amputation. And so you can Google it if you have the stomach for it. There are many pictures if you just Google “Congo Leopold amputations”, you’ll see many pictures of people missing limbs and hands and feet and were expected to continue working. But those were used as punishments and threats to other folks around them that they were not the people in charge, that they didn’t have agency or control over their own lives. Which was certainly something that Maria would’ve been familiar with having come from the abuses and the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade.

And so how do you talk about that? One of the challenges I faced writing for ages four to seven is how do you talk about those kinds of atrocities in a way that little minds can get there, they can grasp, but that it’s not going to put fear in them, but hope. And so Isabel Muñoz, who’s done our illustrations, had a fantastic pen. And I asked her, I said, “When the children,” there was one panel in the book when the children gather around Maria’s home, which she created for them, the Pantops Home for Girls. I said, “When the children are around her,” and we talk about them flitting around her house like little butterflies with purpose and meaning, and they’re finally safe, they’re safe, they’re warm, they’re fed, they’re loved, they’re learning the principles of Christian life. I said, “Can you make one of the children without a hand?”

I just think it’s brilliant the way Isabel did that for us. And if you want to expand the conversation, you can bring that up with your little one. And if they’re not ready for it, you can skip over it. But we need to know the scope, I think, the scope of God’s redemption, the scope of what he’s ransom these children from.

It wasn’t Maria doing the ransoming, it was God ransoming these children from spiritual death, from physical death, from physical mutilation. And he’s doing it through Maria Fearing. So it’s just a little Easter egg for you to look for in the book to help you over those more difficult conversations. What is slavery? Why were these people allowed to have their agency taken away from them? Why are people so cruel? These are the more difficult conversations that a story like Maria’s opens up for us.

It wasn’t Maria doing the ransoming, it was God ransoming these children from spiritual death, from physical death, from physical mutilation. And he’s doing it through Maria Fearing.

K.A. Ellis

Carmen: Karen, when you think about bravery or compassion, when you think about spiritual motherhood and you think about Maria’s life, there’s a lot for us to learn. I think that when we imagine that she not only went from here in the United States as a formerly enslaved person who was by that time well-educated and very accomplished, extremely hardworking, she was a single Black woman. And she then goes to the Congo and she starts, over time, taking in these girls. She paid the ransoms of kidnapped children and enslaved children. She purchased their freedom out of the rubber and the ivory trades. When you think about her agency and how empowered she was, she’d be unusual today, how unusual was she in the late 1800s?

K.A.: There were a number of very intrepid African-American missionaries who are being reclaimed there. Of course, most people would know George Liele. Most people are coming to know the Sheppard team. There is a wonderful book in this series about a woman named Betsey Stockton. A different era, but the whole series is wonderful. I highly recommend. They’ve got Amy Carmichael, Betsey Stockton, just some really interesting unearthings and presentations of these women, it’s called Do Great Things for God.

And the whole focus is that these are ordinary people. These are people whose knees knocked when they were asked to do something courageous, but their faith in God, whose knees do not knock, overrode their fear. Courage, the way we understand courage today, I think, you talk about romanticizing missions, I think we’ve romanticized courage. Oftentimes, I think we are not aware that when we do the most mundane things, we’re making history. We’re making history in eternity when we sow into the kingdom.

And so there were many intrepid people like this who took these incredible risks and leaps and did unusual things. But when you think about it, they’re no more unusual than the tedium of getting up in the morning and doing the things that God has simply asked us to do. It’s just about being obedient. The obedience to me, I think, is the greater marvel. It’s obedience to do whatever is in front of you, whatever you’re being asked to do, and trusting that that’s going to make a dent in eternity when we get there, that we can see when we get there. And that’s all I hope for at the end of my life, is to make some kind of dent in eternity that I can see when I get there.

And it may come from having written a book or it may come from just having the courage to open my mouth and speak up for the truth of God in some hidden-away place that no one will ever see. But God sees. I think that’s one of the most important lessons that I take away from Maria’s life, is that he sees. He saw her, he saw her and her deeds, no matter. He saw her deeds the same way she was on that plantation living under those conditions, the same way that he saw her acts in Congo. And there’s no difference in them. They’re both courageous. They’re all courageous. They’re all significant in his kingdom, whether great or small.

I think that’s one of the most important lessons that I take away from Maria’s life, is that he sees. He saw her, he saw her and her deeds, no matter. He saw her deeds the same way she was on that plantation living under those conditions, the same way that he saw her acts in Congo. And there’s no difference in them. They’re both courageous. They’re all courageous. They’re all significant in his kingdom, whether great or small.

K.A. ELLIS

Carmen: Karen, it feels like on this Juneteenth I would be remiss not to ask, how do you reconcile so many of these threads as a Christian who is also Black and female in America today? And I guess I’m thinking about the Winston family who claimed ownership of the Fearing family and taught her the Bible stories and the Presbyterian catechism, but also did not voluntarily free her or her family. How do you reconcile that?

K.A.: Well, I am a descendant of the slave trade. I’m an American descendant of slaves myself. I could show you a picture of the plantation where my family was held. And the way that I hold these things together as an African-American Christian woman is to know that when we suffer in life, we don’t suffer for no reason. That’s funny English, but let me break that down for you. The suffering that has been introduced in this world by our hands, by sinful man, is redeemed by God in some way, shape, or form. So when I say we didn’t suffer for nothing, there’s purpose and there’s meaning to it. And that’s the beauty of what God infuses into the horrific unjust agency-robbing slaving system, and enslaving systems today. He is still making beauty for ashes.

And that’s one thing that I see in my family’s story. My family has a huge legacy of both faith and education. And I walk strongly and boldly in that. I walk boldly in paths that they set out for me under adverse conditions, horrific conditions. And I know that, the way that he has used Maria’s conditions and the origins of her story to show forth his grace and his redemption. The beauty of him taking a woman, or a team of people even, who were familiar with slavery, transplanting them into a whole different place and saying, “We know these waters. Let us help. Let God use us to help.” And that’s just a string, it’s a breaking of a chain and a building of a string of redemption and hope in my mind.

And so that’s one of the things that I find compelling about Maria’s story is God’s ability to redeem even the worst situations, which is that’s the message of endurance. That’s the message of Christian endurance. That’s how the kingdom ball gets passed forward from generation to generation is these hopeful people who are able to say, “This is horrific, but even when I cannot trust that you are still working, that you are still doing, there are other people around me who are trusting for me.” And that way we can pass a decent kingdom ball forward to the next generation and hopefully leave a little bit less toxic waste behind us of our own sin and our own folly in our own generation.

Listener’s Guide: What’s Next?

Before you quickly move on to the next thing on our to-do list, let’s take a moment to pause, reflect on what we have heard and consider what God may be asking us to do in response.

Reflect

- When we hear about extraordinary missionaries, it can be easy to romanticize their stories as exceptional and distant from our own lives— but really, Maria was an ordinary person who chose to obey God and follow His call. As Karen shared, “The obedience to me, I think, is the greater marvel. It’s obedience to do whatever is in front of you, whatever you’re being asked to do, and trusting that that’s going to make a dent in eternity…” What might God be asking you to do— right here in front of you today— to make a dent in eternity?

- Maria’s story is ultimately about “God’s ability to redeem even the worst situations.” Karen encouraged us that this incredible hope is the story of Christian endurance. Where do you need hope today as you endure challenges?

Pray

- Pray for eyes to see and a heart to follow how God is calling you to obey Him and sow seeds into His Kingdom for eternity.

- Pray for God’s redemptive work in your own community and neighborhood.

Act

- If you don’t know the names of the African American missionaries mentioned in this interview, take a moment to learn more about them — starting with Maria Fearing, William Sheppard, Alonzo and Althea Brown Edmiston, George Liele, and Betsy Stockton.

- Maria travelled to the Congo to ransom children from the slave trade. The evil of human trafficking continues, even today. Consider how you might connect with organizations working around the world to free slaves, such as the International Justice Mission.

Featured Photo by Niklas Weiss on Unsplash